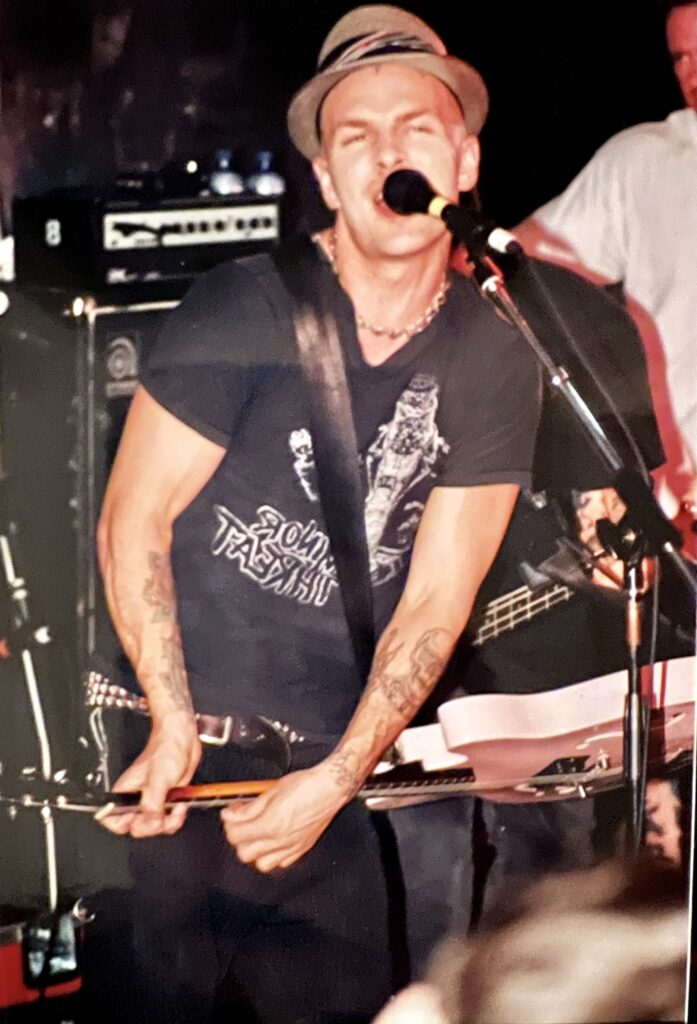

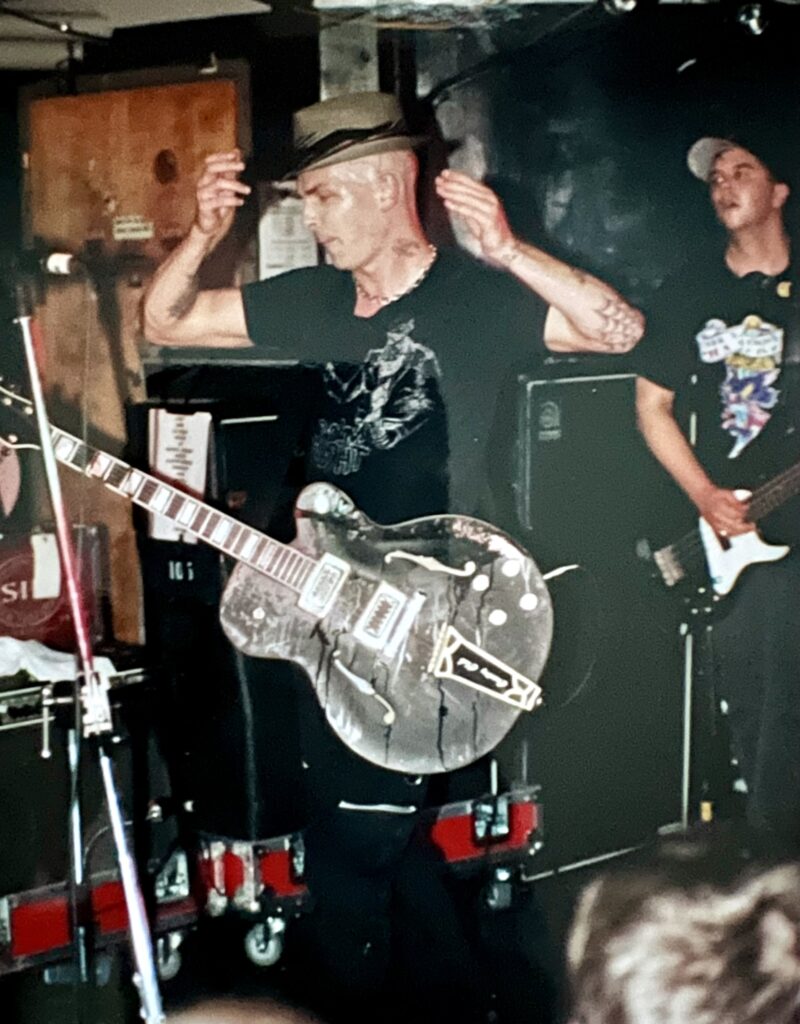

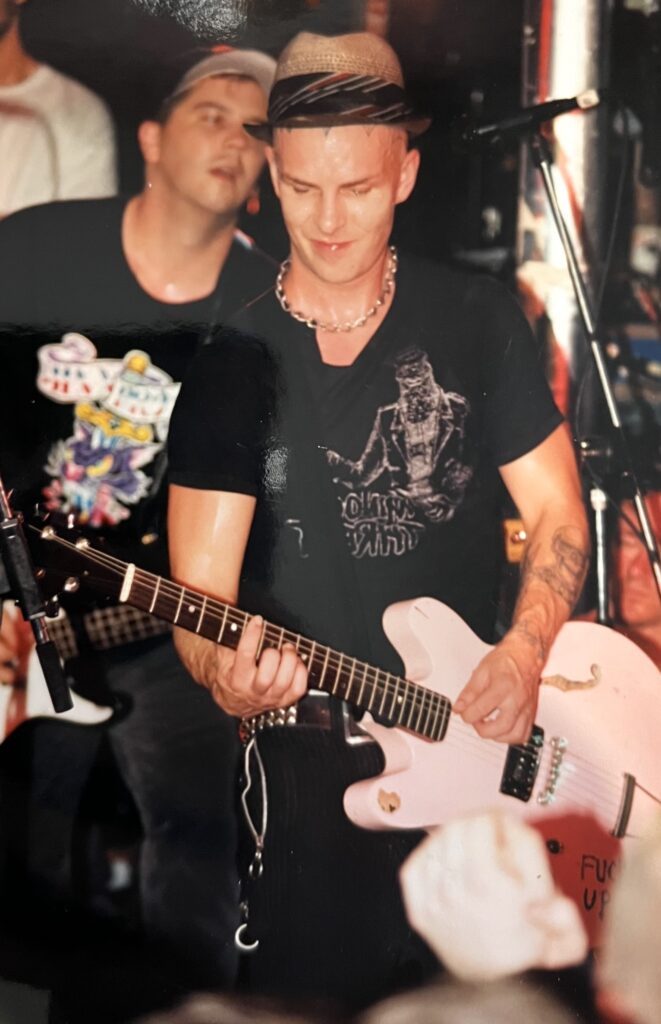

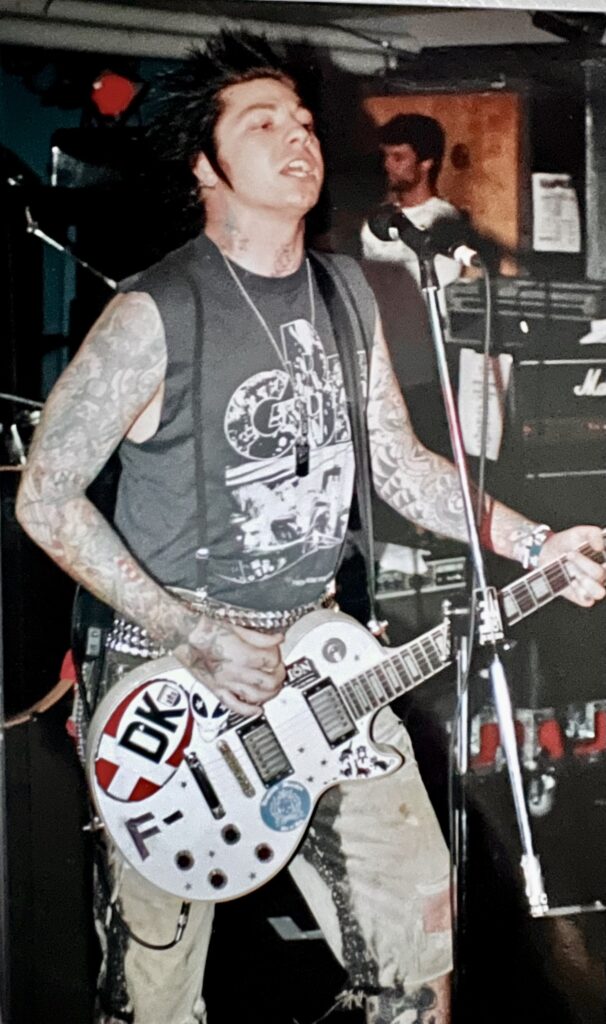

Interview with Tim Armstrong, Matt Freeman, Lars Frederiksen, Brett Reed and Vic Ruggiero from the Slackers, interruptions by Brad Logan from F-Minus, The Wix.

This article was originally published in RUDE International in 1998. The full transcription of the interview (included below the article) was previously published on PinUpNYC.com

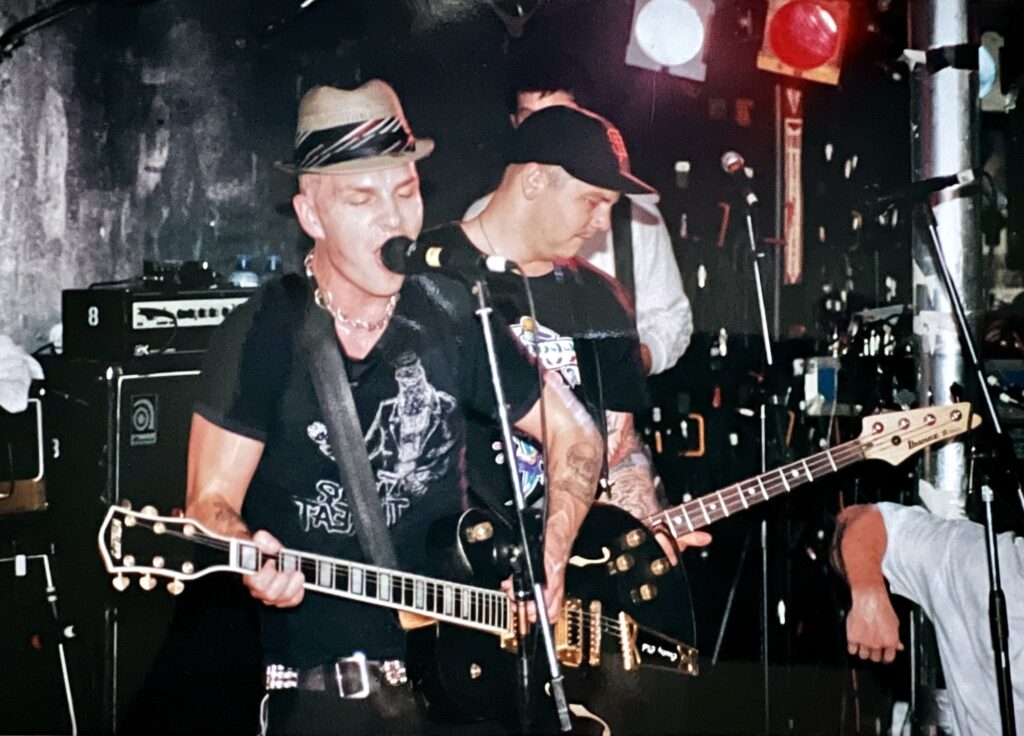

Rancid is, without a doubt, the biggest punk band of the ’90s. With four albums released between 1993 and 1998, co-headlining stints on two of the summer seasons largest festivals, Lollapalooza in 1996 and the Warped Tour in 1998, a slot on the Tibetan Freedom Festival in 1997, and heavy radio and MTV airplay of singles off three of their albums, they still remain one of the most universally loved bands of the underground scene. Rancid’s records at once seem a reflection of the times, as much as they also manage to affect the course of punk with every new release.

Rancid’s newest addition to the punk rock canon, the hefty 22-song Life Won’t Wait, is an album that it is studiedly universal. Comprised of sessions recorded in San Francisco, Los Angeles, New York, New Orleans, and Jamaica over the course of a year, Life Won’t Wait is an incredibly current album, heavily representative of the dynamics of the musical scenes that Rancid are immersed in. It features guests as divergent as Vic Ruggiero and Dave Hillyard of the Slackers, Marky Ramone, Greg Lee and Alex Desert of Hepcat, Jamaican dancehall legend Buju Banton, Lynval Golding, Neville Staples and Roddy Byers of the Specials, Dicky Barrett of the Mighty Mighty Bosstones and Roger Miret of Agnostic Front.

The musical genres of punk, ska, Oi!, reggae, and hardcore; each with their distinctive sub-genres and spinoffs, can only be properly lumped into an overall subculture when pitted against the stronghold of the mainstream. These individual styles have enjoyed fruitful marriages in the past, at times. Yet each has, for the most part, maintained strong, undiluted bloodlines over the decades.

It is only now, for a variety of reasons including the breakdown of communication barriers due to technological advancement, and the many grey areas in between, that interplay between these scenes has begun to increase. The lines are becoming more blurred than ever before. It is no secret that each genre finds its roots in similar soil; reggae is an offshoot of ska, punk is a descendant of rock and roll, as Oi! and hardcore are variations of punk, but at no other time in the last two decades has there been such a unified underground. Until now, there has not been a band so representative of, or an album that so sonically articulates, that unity than Rancid and Life Won’t Wait.

The new album marks the end of a two-year hiatus for the band. Although the past years haven’t exactly been calm for Rancid, things are starting to come fast and furious again, which is fine by them. Rancid kicked off the release of the record with a string of last minute, unannounced warm up shows on the East coast, giving some of their fans the chance to see them in the more intimate setting of a club rather than the stadium festival atmosphere of the Warped Tour. In the few days between the warm up shows and the start of the Warped Tour, I flew out to Los Angeles to catch the band in the lull before the storm.

L.A. is home base for Rancid. Epitaph Records is headquartered there, as is Hellcat Records, singer/guitarist Tim Armstrong’s imprint label. Armstrong has set up residence with his wife Brody in a house not far from Epitaph. His home studio, Bloodclot Studios, is built in the basement.

Although Rancid’s other lead singer/guitarist Lars Frederiksen and his wife Megan live in San Francisco, they came up to LA so that Frederiksen could prepare for the tour and the whole crew could spend some time together.

In the morning, Brody and Megan picked me up at my hotel and we headed out to Rancid’s rehearsal space, about a half hour outside of L.A. Believe it or not, the band gets nervous if people watch them while they rehearse. So to kill some time, we emptied our pockets of quarters playing video games in the outside hallway, waiting for them to take a break. Eventually Armstrong came out and invited me into the rehearsal space, a spacious room filled with equipment and instruments.

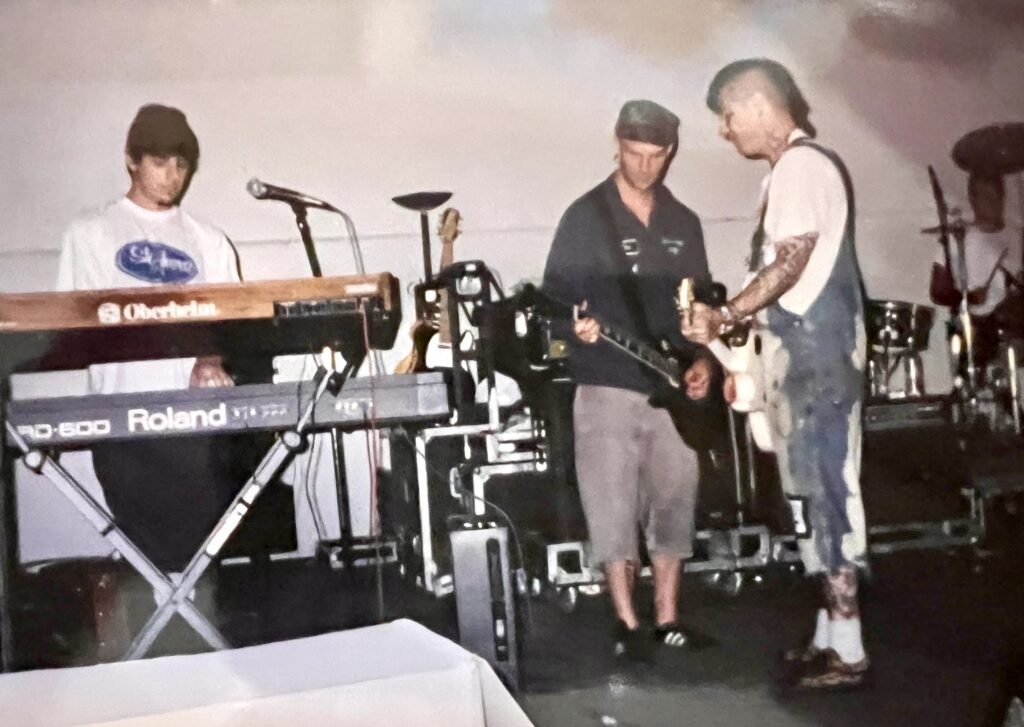

Vic Ruggiero, vocalist for The Slackers, was on one end of the room, playing around on a keyboard. The band was sprawled out across two couches in another corner, surrounding a low table littered with CDs, soda cans, and wrappers on which I set my tape recorder.

Bassist Matt Freeman and Armstrong were the most outspoken on this particular day, and conducted the better part of the interview with me. Freeman is a solid guy, very down-to-earth and articulate. Armstrong is a bit harder to pin down. His infamous spiderweb scalp tattoo was covered by a bandana and baseball cap, leaving his most noticeable feature his expressive blue eyes. At times, he came across as almost painfully shy and reserved, yet moments later, he’d be the loudest one in the group. When I played back the tape, there were sections in which he spoke so quietly, it hardly registered, though he was sitting next to me. There are other times where he’s talking so animatedly, he’s the only one you can hear.

I’d met Frederiksen a few times previously over the years, and each time he’d been very talkative and friendly, but on the day of the interview, he seemed distracted and a bit distant. Brett Reed, Rancid’s drummer, spent the first half of the interview quietly lying on the floor. When he got up and joined in the conversation, however, he was the most entertaining.

Reed’s got a dry, sarcastic wit that doesn’t come across as overbearing, he’s just incredibly honest. They all are. The only defining element that runs through the entire group’s personality is their sincerity.

As people, they’re self-assured, as a band, they’re humble. In conversation, it’s obvious they spend a lot of time together. They play off each other easily and even in the atmosphere of a question and answer interview, the conversation is never stilted. They move smoothly from more serious discussion of their career and the new album, to current projects like the Silencers, to horror movies, Steven King, children’s television programs from the 70s, conspiracy theory and Masons, all in the course of an hour.

Rancid has had its share of detractors over the years. With the rise of Epitaph Records practically overnight from a small indie label to something strongly resembling a major, Rancid, along with the rest of the punk scene, found itself going through some heavy growing pains. Armstrong and Freeman had laid their foundations in 1987 with the band they formed together, legendary ska-punk misfits Operation Ivy. Operation Ivy broke up in 1989, largely based on the band’s discomfort with their success. The band was a vital part of the East Bay underground scene that centered around the Gilman Street Project. When Operation Ivy disbanded, Armstrong, who had been struggling with addiction and depression, found himself with nothing better to do than fall deeper into his problems.

“Rancid was actually formed to give me something to do. Me and Matt to play again. We started it after I OD’d like three times, in the hospital, I was a mess.” Armstrong recounts. “So, that was basically a way to get me going. Brad, Matt and I. Once I had a place to live… I was having a hard time keeping it together. That’s all I wanted to do, my sights were set really low. Just to play some parties, squats in Oakland or punk rock houses in West Oakland, Gilman Street. We just started out telling people, yeah, don’t get your hopes up, it’s not Operation Ivy. Or I would tell people that.”

Armstrong and Freeman formed Rancid in September of 1991, recruiting Armstrong’s roommate, Reed, as their drummer. The trio released its first single on the Berkeley-based Lookout! Records in 1992, and they signed to Epitaph Records soon after.

“Lookout! was more on Green Day’s dick at the time. Laurence Livermore told me, in retrospect, he wished he’d signed us, but… at the time they were all about MTV, Green Day bein’ jackassy.” Armstrong explains. “I had no idea we were gonna sign to Epitaph. Brett [Gurewitz, president of Epitaph Records] heard the tape, he heard the demo. He said it was the best thing he’d heard in three years, which was a nice thing to say.”

Rancid released their self-titled debut on Epitaph Records in 1993. At the time, Epitaph was a small indie label owned and run by Gurewitz, guitarist for the seminal California politico-punk outfit Bad Religion. With the addition of Frederiksen as a second singer/guitarist in 1993, and the release of the band’s 23-song sophomore album Let’s Go in 1994, Rancid’s career was gathering momentum. Punk had begun to make a “comeback” upon the mainstream consciousness, to the derision of public media and punk purists alike.

In 1994, Rancid’s Gilman Street contemporaries Green Day and the Offspring found themselves in the Top 40 practically overnight. Green Day’s breakthrough MTV buzzbin hit “Longview”, followed by the Offspring’s meteoric rise to the limelight with their single, “Come Out and Play” focused national music media’s attention squarely on the Berkeley/Gilman Street scene. The Offspring, an Epitaph band at the time, were the first punk band to sell a million albums on an independent label. Rancid themselves were caught up in the whirlwind, when their single and video for “Salvation” charted soon after.

Rancid headed off for a worldwide tour. On arriving home, for a brief period, they considered signing to a major. They ended up staying with Epitaph, a decision that they say has given them the freedom and the support to succeed beyond their expectations.

Armstrong explains, “We’re in a position of making records at Epitaph, doing ’em one at a time. All these bands owe like seven records to their record label. It’s fucking scary. We don’t have that shit loomin’ over us. If no one buys this record, well alright, we’ll do another one. If Epitaph doesn’t want to do this record, we’ll go put it out on Lookout!, you know what I mean? That takes a lot of pressure off of us.”

Rancid’s next release, 1995’s …And Out Come The Wolves, was an accomplished album. Its first single, “Time Bomb”, kicked down the door to make way for the rise of ska-punk and third wave ska in the mainstream, for better or worse. One of the highlights of the album was a guest appearance by punk oldtimer and poet Jim Carroll, whose line in “Junkie Man” became the album’s title.

The band met Carroll when they were recording the last of the vocals for the record in New York. Carroll was doing an interview upstairs from them, and word came that he wanted to meet them. Freeman recounts, “We asked him, ‘do you want to sing on the record?’ He’s like ‘yeah’, so he comes down right after the interview, hears the song once – boom – there’s the lyrics. Goes in, does it, we watch his video premiere on MTV for “The People Who Died” and then he left. The whole thing took place in half an hour.”

“Like everything, it was an accident,” Armstrong adds, “The whole band is an accident. I’m serious. All this shit’s an accident. Runnin’ into Buju Banton was an accident, runnin’ into Jim Carroll was an accident. We didn’t go down to Jamaica to meet Buju. We ended up at his house, but we didn’t plan any of it.” Oddly enough, Buju Banton’s line in “Life Won’t Wait” became the title for that album as well.

Rancid’s members share a common obsession with conspiracy theories and an affinity for horror movies. Coupled with the fact that they have all gone through varying bouts of drug and alcohol addiction and depression, these influences give Life Won’t Wait a very dark, haunting edge. Although the album contains punk rock love ballads and hopeful, anthemic tracks, there is also a deep paranoia running through it, an Armageddon-like feel to many of the songs, especially the more heavily political ones.

There is a deeply personal element to that dark side. Rancid stands apart from other bands who generally find themselves bandmates because of musical commonalities and who sometimes, in light of hardship, stay together for the sake of the band and the music. Rancid say they exist as a band and make music because they need it to keep them alive.

At some point or another during the interview, each band member separately stated that either the music itself, Rancid as an entity, or the individual members of the band had saved their lives. This love and respect for each other allows them to give each other enough room to create their own strikingly individual sounds in the symbiotic whole.

The content of this album, both musically and lyrically, is no surprise looking back at Rancid’s many endeavors and projects during the better part of the last two years. While most people take breaks to rest and go on vacation, Rancid have spent their free time doing what they love most — making music. They each, in their own way, have taken the opportunity to use their influence and ability to help out those around them. The result of those projects has been some of the highest quality music coming out of the scene today.

In the last year, Lars Frederiksen has produced two exceptional Oi! releases, the Dropkick Murphy’s Do or Die and the Business’ The Truth, The Whole Truth, and Nothing but the Truth. Rancid has lent their talents to standout tracks on a variety of recent albums from the Specials, Agnostic Front, The Stubborn All Stars, Buju Banton, and Dr. Israel.

Matt Freeman’s signature growling bass line showed up on X frontwoman Exene Cervenka and drummer DJ Bonebreak’s sideproject band Auntie Christ. Tim Armstrong filled his spare time during Rancid’s hiatus harvesting the cream of the crop of American ska, punk, and Oi! bands: the U.S. Bombs, the Gadgits, the Pietasters, The Slackers, the Dropkick Murphys and Hepcat, and planting them all lovingly on Hellcat Records.

Although the band itself may be an accident, there is no accident to Rancid’s success. As an individual band, and as members of a cultural community, they understand the importance of supporting a scene from the bottom up. Of showing respect for those who have come before, remembering the people who helped them out when they were down. Among the few who are lucky to find themselves in such a position to reciprocate, Rancid stands out as a band that holds that top priority. It’s the truth of their conviction, the truth of their actions that come across so honestly in their music.

On Life Won’t Wait, Rancid finally have come fully into their own to produce a stellar album that encompasses ska, reggae, dub, r&b, blues harmonica, acoustic piano, straight up rock and roll and the howling undertones of street punk and hardcore. All this in the broad sweep of a quintessentially punk album.

There are throwbacks to artists ranging from the Pogues to Lee “Scratch” Perry, and yet each one is treated with respect, not only by Rancid’s technical execution of the styles, but the way in which they throw their individual twist on it. So many other bands get by on mostly apeing what’s already been done. Rancid take their cue from the artists whom they most admire, pay more than due respect, and move on, taking something old and making it current and new by adding their own genius to the mix.

Rancid Interview Transcription

Interview with Tim Armstrong, Matt Freeman, Lars Frederiksen, Brett Reed and Vic Ruggiero from the Slackers, interruptions by Brad Logan from F-Minus, The Wix.

Do you feel that when music and creativity become business, which it inevitably does, do you find it hard to stay close to the fact that at its true heart, it’s meant to inspire, to save and to give? Do you find it hard to separate the craziness of the industry from the fact that music is so powerful that a band, a song can change or save someone’s life?

Tim – Well, you gotta stay humble and grounded. Humility is a great gift. Try not to let it go to your head. I’ve known all these guys for a long time and when one of us starts to bug out, the other person is there to check ‘em and bring ‘em back down. There’s no superstars in this band, we’re all on the same level. We all get paid the same, it’s all equal and that’s a pretty healthy place for us to be.

Matt – I think it’s important. There is a total big difference in both aspects of it. I don’t think we ever really gave a fuck about money or success. I think success was always, to us, being able to get some food.

Tim – Not even that, for me, just to make a tape. Success was making a tape. I spent my last five dollars on making a couple tapes.

Matt – Having some money to put up a flyer.

Matt – Yeah, I don’t think it’s really hard for us to differentiate the two.

So you don’t find yourselves in any position that makes you feel that way.

Tim – You know, we’re in a position of making records at Epitaph, doin’ em one at a time. All these bands man, they owe like seven records to their record label, it’s fucking scary. We don’t have that shit loomin’ over us. This record, if no one buys this record, well alright, we’ll do another one. If Epitaph don’t wanna do this record, we’ll go put it out on…um.. Lookout!, you know what I mean? That takes a lot of pressure off you, it really does, man.

Matt – It’s all how much you let it get to you. If you buy into all the fucking bullshit and think you’re like… You know a lot of people always try to fucking kiss your ass or blow a bunch of smoke up your ass, in a way of speaking. If you believe that and stop respecting the craft, I mean really, and stop respecting where you came from, stop respecting the people who buy your records. Doin’ all that shit, you’re bound just to fucking fail and that’s when you start fucking up. If you, like Tim said, just stay humble, and be thankful and do the best you can. Again with us, what he said was completely fucking true. We only have one record at a time and if this one doesn’t do good, who cares, we’ll just do the next one. So that’s the way you do it, you know?

Lars – As long as we’re happy with what we did, that’s all the most important thing for us… Two fingers in the air, you know what I mean? Because where we come from, I think we’re all in tune with it, it’s just right around the corner, you know? Like Tim was saying, humility, you gotta bask in it.

When you started Rancid, do you remember the vision, either musically or aesthetically that you had for the band?

Tim – It was actually formed to give me something to do. Me and Matt to play again. We started it after I OD’d like three times, in the hospital, I was a mess. So, that was basically a way to get me going. Brad, Matt and I. Once I had a place to live… I was having a hard time keeping it together. That’s all I wanted to do, my sights were set really low. Just to play some parties, squats in Oakland or punk rock houses in West Oakland, Gilman Street. We just started out telling people, yeah, don’t get your hopes up, it’s not Operation Ivy, or I would tell people that. It’s the same thing I said like, this really started out humble, we just really did. I had no idea we were gonna sign to Epitaph.

Matt – No, that wasn’t even thought about.

Tim – Brett heard the tape, he heard the demo. He said it was the best thing he’d heard in three years, which was a nice thing to say. We did this thing on Lookout!, but they were more on Green Day’s dick at the time. Lawrence Livermore told me, in retrospect, he wished he’d signed us, but… At the time they were all about MTV, Green Day bein’ jackassy, you know what I mean? All those bands… I like Green Day, though.

What do you feel like you get from the scene, what do you feel it gives back to you? I know it’s hard to separate, your whole lives are intertwined…

Lars – A place to go, whether it’s a show or a record, you can go there. I think all of us, if we didn’t have a record or a turntable we’d probably all be dead. I think it gives us a sense of belonging, whether it was Black Flag or the Ramones or whoever. Or bein’ at the gig, involved. We got so much from it, you got like an identity through it, a family from it, you know what I mean? I think that’s important. For instance, Hellcat Records, that’s like givin’ back to the scene. That’s a perfect instance of like, ‘thanks, here’s something else, here’s something back… much respect.’

Tim – Yeah, that’s true. He’s right. Lars produces bands, helps out a lot. Matt was in Auntie Christ, a Lookout! band.

I talked to Exene. She was really on about it, she said ‘he helped me out so much, it was so nice’…

Tim – Really?

Matt – That’s nice of her to say.

Lars – I listen to any one of those Hellcat bands and I get the same feeling when I listen to a record… I feel like it’s me in that band, me in that record. If it’s still happening, that’s great. It’s really easy to become jaded, you know, ‘I was there before… you know, blah blah, punk rock in ‘65.’

Tim – Nah, man. Do you like uh… do you like the Slackers?

Yeah.

Tim – You should interview him a little (points to Vic Ruggiero) ‘cause he’s playing with us. Ask him a question, huh? Hey, Vic!

Vic – Yo!

Tim – Come here for a second.

Matt – Hey, Boo Boo!

Vic – What’s up?

Tim – So, uh, we gotta get a quote from you because you’re playing with Rancid.

Vic – What, a quote? A boat?

Well, actually, I meant to ask, you guys are doing something with the Silencers?

Tim – Yeah, me and Vic and Matt are in a band called the Silencers. We tracked like, how many tracks that first day? The first two days?

Vic – A lot.

Matt – Like eight…teen.

Vic – In the first three days we did like twenty.

Matt – I don’t know, but it was a hell of a lot.

Vic – It was somethin’ around eighteen, nineteen.

Tim – Yeah, and we’re still kind of looking for a singer for the Silencers. ‘Cause I sing on the track on the Give ‘Em the Boot comp. What we did yesterday is we put vocals down for a couple of the songs. Wix sang some songs yesterday, too, for one. And we split one. We’re kind of going to record all those songs and try to find someone to sing it, does that make sense? What probably will happen is we’ll end up just keeping what we did and just put that out.

Vic – It would be cool to have a whole bunch of different people do the shit.

Tim – That’s true.

Vic – That would be the shit.

Tim – Well, that’s kind of happening.

Vic – Like the house band.

Tim – We had Mad Lion come in and he wrote lyrics to the hard dancehall tune. Like Rancid with Vic but for the Silencers, like an outtake we never used… I wish I had the tape, but I just gave it away. I have the dat at my house.

I heard this demo that you did awhile back, before the album.

Tim – Yeah, Vic played on that.

Some of the songs were incredible. I was wondering why you didn’t use them on the Rancid album. A few of the songs off it you did, like Cash, Culture and Violence, but you changed it, it was more stripped down on the demo. How come you changed it so much?

Tim – Well, we did the demo. This is when I moved down to LA and started Hellcat. Vic was down here, Vic came out to play on it. What happened? Cash Culture had this real funky like Josh Freese beat. Matt should probably answer this question. We tried to do Cash Culture kinda like that, but it never really worked, so by the end of the day we were like ‘fuck it’, and we just did it the way Rancid would do it. Some day I might want to release that on Hellcat. The demo sessions.

Vic – Well, those were just demos, right? For the fucking, for the Rancid record. Demos are like however they come out, they come out. It wasn’t intended necessarily to be specifically that, right? That’s kind of what I figure.

Tim – Vic’s great at the demos because he can play everything. Lars tried to play bass and Vic plays guitar, and Vic plays the piano and percussion, and what else do you play?

Vic – That’s about it.

Tim – B-3.

Vic – Piano and guitar.

There’s a lot of piano.

Tim – On the demo, huh?

Yeah.

Tim – Yeah, it’s cool.

Matt – Cash, Culture and Violence was sort of hard because the song had a vibe to it. We tried to do it, the vibe was there, and I couldn’t really copy it on the bass. I tried several different things and finally it just turned out the way it did.

Vic – But that bass line you got now is fucking kick ass.

Matt – Yeah, that’s me… angry at you.

Tim – (laughing) We’re recording Cash Culture, right? At first, we had the original stuff and Rancid was just kind of playing over it, you follow me? Okay, so Matt’s there. He was so mad ‘cause I kept wanting to play Vic’s bass line, and Matt’s a great bass player. Him and Vic are on two different levels, wavelengths… two different artists, respectively so. Matt was like, he got so mad at Vic that he wouldn’t even say his name. The bass was in the headphones and he was like, ‘Teach!’…who was the engineer… ‘Teach! There’s some other guy… Bass! There’s some other guy in my headphones! Take him outta there! Some other bass player in my headphones!’

Matt – ‘Cause you listen to that track, the one that’s on the record, and I’m just like diggin’ into the fucking strings. I mean, I’m definitely like, ‘I’ll show you how to play it, Mr. Ruggiero! You know, I’m just like dunna dunna dunna dunna let’s see you try to do this, you fucking hippie!’ It was pretty crazy, the track made the record.

Tim – ‘Cause Vic’s like, if you listen to it, his bass tracks, he doesn’t play the same thing twice. It’s cool. Freeman’s more where he gets locked down to something, it’s just solid. Two different styles.

Matt – (to Vic) You more do improv shit.

Vic – Yeah.

Matt – I’m sort of like a pit bull when it comes to bass lines. I grab on and don’t let go.

Tim – Vic goes far East with it, you know what I mean?

Vic – Far East, man.

Tim – He does.

Vic – (to Matt) But your tone is a lot different. You like that real sharp tone.

Matt – Brother, I tried your tone. I tried everything, I couldn’t do it. I almost cried, I was just like, I CAN’T DO THIS.

Vic – It’s a different approach. My mom likes your bass playing a lot, by the way. My mom only likes Charles Mingus and Motown, James Jamison bass playing, she don’t like anybody. But she was like, ‘Yo, that guy playing bass.’ She was like, ‘Vikta is dat you playing bass?’ I was like, ‘naw.’

Matt – (yells) No it’s not! It’s me, Matt!

Tim – (laughing) She thought it was you playing bass on the Rancid record?

Vic – Yeah, on one of the tunes. And I was like ‘naw, that’s this guy Matt’, she was like ‘Wow. He’s a very good bass playa, you know. He’s very very good.’

Matt – That opened my eyes though, man. Yeah, I started practicing a lot… On that record I changed my style a lot. I started playing with my fingers for the first time.

Tim – Yeah, the demo kind of upped the ante. I mean, here I was hangin’ out with these great New York bands, Vic and all those. Rancid… it kind of took it to another level for us. That demo kind of launched the whole record and these guys, they had to match it, they had to play better than the demo.

Matt – It definitely lit a fire under me, got me going.

What about other people who played on the album?

Tim – Yeah. Dicky Barrett, Hepcat sang on Life Won’t Wait. Buju Banton, he’s like the king. Man, he’s so talented. The Specials, they were cool, heroes of mine, the Specials. The Specials were like punk rock, you know what I mean? Vic and I talked about this before. They weren’t really like ska, they weren’t really rocksteady or oldschool, they were almost like English punk, fast. It wasn’t really ska, they created their own sound. Their own kind of music, Two Tone. The Specials were almost like soul, you know? A lot of that stuff. The bass player played disco bass lines.

Matt – Yeah, he did actually.

Tim – You know what I mean? Like what the fuck was that? I never heard any ska records with like a disco octave…um dat um dat um dat…

Do you guys want to talk at all about the strong political streak in the record? To me, this record is intensely political. I can’t figure out all the words, but…

Tim (jumping up) – You can’t understand the words?

Naw, some of the words I can’t figure out and you guys didn’t give us lyrics.

Tim – You can’t, you can’t hear it?

A lot of them I can…

Matt – It’s like the most decipherable vocals..

Yeah, this record is way better than the others. I don’t mind it but, honestly, on some of ‘em, I can’t understand all of it. Maybe when I listen to it on headphones it’s better, but…

Lars – That’s the beauty of it, it’s like an old reggae record. You gotta listen to it a hundred times before you can actually hear it.

Tim – Like an old dancehall record. Listen to a B-Man(?) record, tell me what he’s sayin’. You gotta listen to that kid a bunch of times, then you can understand it, and all of a sudden it just hits you.

The more you listen to it, each time, you catch something you didn’t notice before. A lot of it feels really bleak, Armageddon-like. This album is partially darker, not wholly darker than what you’ve previously done, but it’s dark.

Tim – It is the most political record we’ve made.

Do you mind talking about it at all?

Tim – I’d like to get some Gatorade.

Matt – Will you grab me a water while you’re over there?

(Tape stops)

(Tape starts again)

Brett – …What came on after Wild Kingdom?

Lars – The Muppet Show.

Matt – That’s true, yeah, Sundays. Remember Wonderful World of Disney?

Brett – Wonderful World of Disney?

Matt – Yeah, you might be a little young for that, that was back in the Seventies.

Brett – Ooh.

Matt – I’m not saying… It was the early Seventies, you weren’t even born yet. I’m talking like ‘71, ‘72.

Brett – Naw, I was about one.

Matt – Atom Twelve was my favorite. (recites) ‘Atom twelve, what atom twelve? See the man.’

Tim – What was your question?

I don’t have any questions specifically dealing with that. You obviously travel a lot, so you’re given the opportunity to be outside looking in at America from a different perspective.

Lars – That does give us a different perspective on world events. Yeah, I think that help us out a lot. Maybe it gives us too much perspective.

Brett – I don’t think any of those songs are really preachy politics.

Lars – We’ve always been sort of personal politics…

Brett – Sharing stories of what’s happening around, you decide what you want from them.

Lars – Some of the songs, like New Dress or Warsaw have a certain thing to it. Whether it’s about Yugoslavia or sending baseball bats over to Warsaw ‘cause they’re trying to teach the Polish kids how to play this American sport, and they ended up taking baseball bats and smashing the shit out of a discotheque. New Dress is just more of the whole kind of Western influence. We always seem to get our hands involved into something. It always has to do with religious or ethnic cleansing.

Do you feel that keeping politics in your music helps?

Lars – I just think we do what comes naturally to us. We don’t try to hide it, we don’t try to do it one way or another. I think the way that we go about lyrics is there’s really no right or wrong words. You can talk about it, but I don’t think we get up on the soapbox and say this is right or this is wrong.

Matt – Hey, Bradley, wanna shut the door, man?

Brett – Barnboy.

Lars – We just talk about what affects us, what we see.

Brett – He’s like an oxen out of the barn.

Matt – Pushin’ that plow.

Brett – Plowboy!

Brad – Hey, only other plowboys can say that stuff.

Just a couple specific things I wanted to ask you about. This may be a little bit of a reach, but the symbol of the wolf reoccurs in a lot of your songs, in Out Come The Wolves it stems from that Jim Carroll poem…

Brett – What everybody doesn’t know is that I was secretly raised by wolves. No, seriously. I was abandoned as a child and they brought me up. I gotta give props to the wolves ‘cause I wouldn’t be here today if it wasn’t for them. It seems to come up in the music every time. I don’t know, I don’t write the lyrics, but… The band’s supporting me, being like my surrogate family and being like ‘Hey, we’re your wolves, we’ll be your wolves. Put some wolves on the record, we’ll make you feel at home.’

Lars – I gotta clean him every now and then with my tongue.

Matt – There was this deer in my backyard and all of a sudden fucking Brett starts biting its neck and I’m like, what are you doing? You’re killing the poor little fucking deer!

Brett – I think it’s coincidence that there’s The Wolf on this record and Out Come the Wolves on the last one. I think, I don’t know.

(Tim comes back)

Tim (very serious)– It’s a symbol. Of the wicked, of the nefarious.

Lars – The wolf on the prey.

About using Jim Carroll on the last album, did you sit down and decide that you wanted to use him, did it just come up?

Tim – Like everything, it was an accident. The whole band is an accident. I’m serious. All this shit’s an accident. Runnin’ into Buju Banton was an accident. We didn’t go down to Jamaica to meet Buju. We ended up at his house, but we didn’t… Jim Carroll…

Matt – We were doing the record in New York. Some vocals, like the last of the record before we did the mix and lo and behold, he’s doing an interview upstairs, and…

Brett – You guys found out that he was upstairs.

Matt – …And we went up to meet him ‘cause he wanted all of us to meet him, but whatever, and we said, do you want to sing on the record? He’s like yeah, so he comes down right after the interview, hears the song once – boom – there’s the lyrics. Goes in, does it, we watch his video premiere on MTV for the People Who Died and then he left.

Brett – I think it took place in half an hour.

Tim – Isn’t that weird? He just came down and wrote lyrics, did like one take…whoo – out.

Are you fans of his work, do you read his poetry? (They all look at me confused and suddenly I’m not sure of whether they know of Jim Carroll as a poet as well as a musician.)

Tim – I’ll tell you another thing. Buju Banton named this record, Life Won’t Wait, that’s Buju’s line. Out Come the Wolves, so did Jim Carroll.

Matt – So when we first started planning this out, we said – Okay, by the third record we’re gonna get guests on it and whatever they say, we’ll title the record.

Lars – But I was noticing about the wolf thing too, because I’m like, out come the wolves, and we had this one song called Lycanthropes which is the technical term for a werewolf, which never made it. So it’s kind of like… we’re fascinated.

Matt – It’s one of those weird conspiracy things they’ll write about in ten years like, who’s the wolf?

Tim – Who’s gonna be on the next Rancid record who’s gonna name the record?

Brett – (affects an announcers voice) If you’re a guest vocalist on the next Rancid record, you can have a shot at the title!

Tim – It’s a contest.

Brett – Come on down!

Matt – Here at KROQ we’re giving away tickets to the new Rancid record. Be the guest and you can name it!

I promised someone I’d ask you what’s your favorite city.

Tim – Kingston, Jamaica.

Someone – I like New York.

Matt – That’s a hard one.

Tim – I like Napoli. Naples, Italy.

Matt – Yeah. I really like New Orleans.

Brett – You like New Orleans?

Matt – I had a lot of fun last time I was there.

Wix – (whispers) Lockport, New York.

Tim – I also like Lockport, New York.

Someone- Wichita.

Matt – I like Boston a lot, except every time I drive there I get fucking lost. (in Boston accent) Go down Storrow Drive, make a left, by the dumpsta.

Someone – Buenos Aires.

Tim – Vic, you must have a favorite city.

Vic – Kansas City.

Tim – Vic likes Kansas City.

Vic – Campbell, that’s where the Ramones are from.

Matt – I like Oakland a lot.

Tim – Elvis Presley’s from Campbell.

Matt – I like Memphis a lot, talking about Elvis.

Tim – What’s your favorite city?

New York.

Lars – Wolvesbain, North Carolina? Wolvesberg, Ohio?

Brett – Salem.

Someone – Hyannisport.

Lars – Where you from?

New York.

Wix – She lives in Boston now.

Lars – What part of Boston?

Allston.

Lars – You know the Silver Bullet pub there?

You’re scaring me.

Matt – Let’s stop picking on Margo, she doesn’t know us that well.

Lars – Poor Margo, all’s she wants to do is this interview and we’re being…

(To Wix) They’ve been picking on me this whole time.

Lars – Where’d she go? What do you mean she only comes out at night, when there’s a full moon?

– Margo Tiffen